Reproductive Strategies

Syllids are an exciting bunch when it comes to reproduction. Not only is there large diversity in reproductive strategy among the family, the strategies themselves are useful tools in the delineation of phylogenetic relationships within the family (see Evolution & Systematics). Epitoky is a reproductive strategy utilised by Syllids, Nereidids and some other polychaetes (as reviewed in Franke, 1999). Epitoky refers to the substantial morphological change that an individual undergoes in order to reproduce (Nygren & Sundberg, 2003). This change can manifest in a number of different ways, though it all leads to the same goal: liberation of the reproductive individual or its constituents from the benthos into the pelagos (Franke, 1999).

There are two forms of epitoky: epigamy and schizogamy, and both occur in the sub-family Autolytinae (Nygren & Sundberg, 2003). Epigamy involves dramatic morphological change of the entire adult animal, from a benthic asexual adult (atoke) to a specialised pelagic sexual adult (epitoke) that swarms, spawns, and dies (Shiedges, 1979; Nygren & Sundberg, 2003). This usually involves the development of specialised swimming chaetae and the enlargement of the sensory organs (Aguado et al. 2012). Schizogamy, on the other hand, involves only a small part of the atoke transforming into one or numerous epitokes via the process of fission (Franke, 1999). In this instance, the atoke, or stock, essentially buds clones of itself, usually from its posterior segments. The clones, or stolons, eventually break off to rise through the pelagos to pursue swarms or mates. The atoke on the other hand, remains on the benthos, ready to produce more stolons when the time comes (Aguado et al., 2012).

Of course, what is biology if not complex? Within the strategy of schizogamy, also called stolonisation, are two forms again: scissiparity, when only one stolon is produced at a time, and gemmiparity, when more than one stolon is produced (Nygren & Sundberg, 2003; Aguado et al., 2012). Gemmiparity only occurs in two genera: all Myrianida and some members of Trypanosyllis, a genus that lies within the sub-family Syllinae (Aguado et al., 2012). It is important to make the distinction here that stolons are not bona fide free-living individuals; they are simply vessels of gametes that exist only for dispersal, copulation, and in some cases, embryo care (Franke, 1999). But once their job is done, they die, and more stolons will eventually rise to take their place.

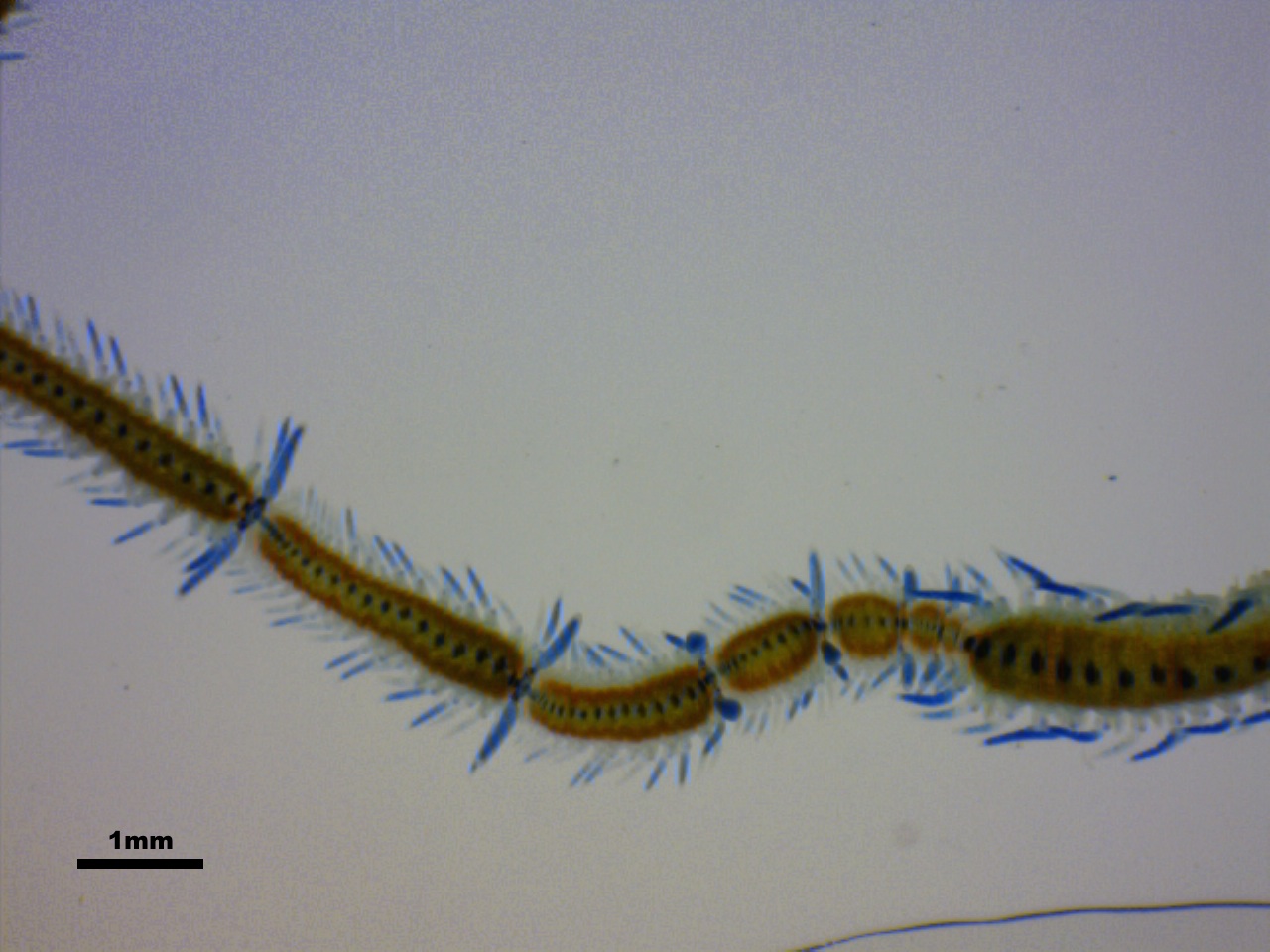

As you have probably already gathered, M. pachycera undergoes gemmiparous stolonisation, producing a long chain of successive stolons, the most posterior stolon being the most mature (Figure 1; Nygren & Sundberg, 2003). Female adults will produce distinct female stolons, and male adults will produce male stolons (Rouse & Pleijel, 2009; Aguado et al., 2012). This gonochorism is essential in the mating behaviour that is to follow.

|

|

Figure 1 Myrianida pachycera undergoing stolonisation. The rightmost body is the stock's with the newest stolons budding from the stock's posterior end. The more posterior the stolon the more mature.

|

|